What the Galimberti et al., 2025 study actually says—and how misinformation about cannabis spreads faster than the facts, and how cannabis and psychiatric disorders is a much more nuanced topic than you might think!

This post is a breakdown of the June 2025 study titled “The Genetic Relationship Between Cannabis Use Disorder, Cannabis Use, and Psychiatric Disorders,” published in Nature Mental Health. Authored by Marco Galimberti, Cassie Overstreet, Priya Gupta, Sarah Beck, Cecilia Dao, Joseph D. Deak, Hang Zhou, Emma C. Johnson, Arpana Agrawal, Murray B. Stein, Daniel F. Levey, and Joel Gelernter, from the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium, International Cannabis Consortium, and the iPSYCH group, the study explores genome-wide associations between cannabis-related behaviors and psychiatric diagnoses. Here, I’m examining what the data really show, what the authors conclude—and where public interpretations have already gone astray.

Table of Contents

- The Poison Apple Problem: How Fear Disguised as Science Misled the Public on Cannabis and Mental Illness

- Why Psychiatry and Cannabis Keep Showing Up Together (But Not for the Reason You Think)

- When Science Gets Stripped for Parts: How Oversimplification Becomes Policy Poison

- From Villain to Healer: Rebuilding the Cannabis and Psychiatry Conversation

- 🍏 A Better Ending

- What the Headlines Missed: Data Points Worth Your Attention

- The Numbers They Never Mention: Cannabis, Genetics, and Psychiatry by the Stats

- 🔎 10 FAQs about Cannabis and Psychiatric Disorders

- 1. Does cannabis use cause psychiatric disorders?

- 2. What’s the difference between cannabis use and cannabis use disorder?

- 3. What is GWAS and how does it relate to cannabis?

- 4. How should clinicians interpret genetic studies about cannabis?

- 5. Why is the endocannabinoid system (ECS) important in this conversation?

- 6. Why do people with trauma or ADHD use cannabis?

- 7. How can studies like Hildebrand 2025 be misinterpreted?

- 8. Is there a safe way to use cannabis for psychiatric symptoms?

- 9. How can we improve cannabis research and policy?

- 10. What’s the big takeaway from the blog?

🍎 What You’ll Learn in This Post

🧬 Why genetic overlap doesn’t mean cannabis causes mental illness

🍎 How scientific nuance gets lost in public messaging

🧠 The difference between cannabis use and cannabis use disorder

🔍 What the Galimberti et al., 2025 study actually found—and didn’t

⚖️ Why fear-based narratives about cannabis do more harm than good

The Poison Apple Problem: How Fear Disguised as Science Misled the Public on Cannabis and Mental Illness

Poison Apples & Panic Posts: When Science Becomes a Weapon

The story starts innocently enough. A scientific paper drops. A few social media accounts with polished language and professional headshots pick it up. A graph circulates. Then a headline: “Cannabis linked to psychiatric disorders through genetics.” Sorry not sorry: cannabis and psychiatric disorders is just not that cut and dry.

Cue the panic.

Within days, that tidy little press cycle becomes a viral, decontextualized truth bomb—repeated by well-meaning parents, skeptical clinicians, and overzealous pundits. The danger isn’t just in the simplification. It’s in the seduction. Because when someone serves you a shiny, data-drenched apple that promises clarity on something as polarizing as cannabis and mental health… who wouldn’t take a bite?

But some apples are laced with something more potent than THC. They’re laced with fear, misinterpretation, and a fundamental misunderstanding of how science—especially psychiatric genetics—actually works.

And that’s what happened with the June 2025 Nature Mental Health paper by Galimberti et al.

The Study Behind the Scare: What Galimberti et al., 2025 Actually Did Say

Let’s start by grounding ourselves in facts. This was a genome-wide association study (GWAS)—a massive statistical sweep across the human genome, looking for patterns. In this case, the team examined whether certain genetic signatures were shared between:

• People with cannabis use disorder (CUD)

• People who simply reported using cannabis (CU)

• And those with major psychiatric diagnoses like schizophrenia, ADHD, bipolar disorder, and depression

The dataset was enormous, pulling from biobanks, global consortia, and diagnostic records. It was also statistical—not clinical. Not causal. It didn’t assess how much cannabis someone used, what kind, why, when, or how it affected them. It simply asked: do these genetic risk factors tend to cluster in the same individuals?

The answer? Yes. But not in the way Twitter wants you to think.

What the Genes Say—and Don’t Say

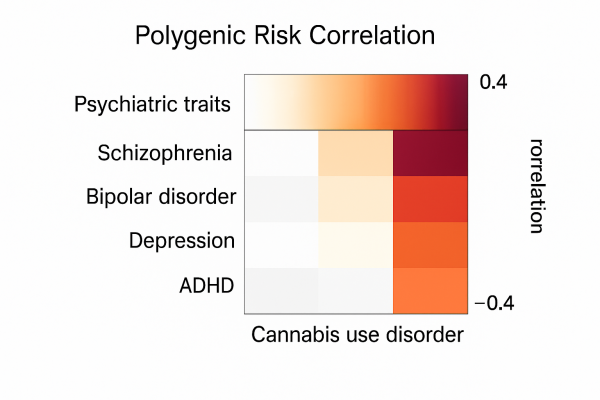

The study found that people with genetic risk for certain psychiatric conditions also had higher polygenic risk scores for cannabis use disorder. Notably, those same psychiatric risks were far less correlated with casual cannabis use.

So what does that mean?

It means that the genetic soup that makes someone vulnerable to depression or ADHD might also make them more prone to problematic cannabis use. Traits like impulsivity, poor emotional regulation, trauma sensitivity, and executive dysfunction don’t neatly respect psychiatric categories—they sprawl. And in doing so, they connect dots across different behaviors, including CUD.

But they don’t prove that cannabis causes those conditions.

In fact, the study explicitly avoids any causal claim. It uses words like “association,” “shared heritability,” and “genetic correlation.” These are carefully chosen terms. They matter. Ignoring them is like mistaking a weather forecast for a storm.

CUD Is Not Cannabis Use (And Conflating Them Is Intellectual Malpractice)

Here’s the trap that caught the internet: cannabis use disorder (CUD) is not the same thing as cannabis use (CU).

You can drink wine and not be an alcoholic.

You can take sleeping pills without being dependent.

And yes—you can use cannabis without having a disorder.

But in the public’s rush to moral clarity, CUD and CU get jammed into the same category. Suddenly, every patient using cannabis for sleep, anxiety, pain, or appetite is at risk of psychosis, because someone saw a scary bar chart on Twitter. The conflation isn’t just incorrect—it’s reckless.

The study itself makes this distinction clear. Genetic correlations between CU and psychiatric traits were much weaker than those between CUD and psychiatric traits. The problem isn’t cannabis. The problem is when cannabis use becomes disordered—and even then, the story is more complex than most headlines allow.

Why Psychiatry and Cannabis Keep Showing Up Together (But Not for the Reason You Think)

Trauma, Vulnerability, and the Endocannabinoid Escape Hatch

There’s a reason cannabis shows up again and again in the lives of people with psychiatric diagnoses—and it’s not because it’s causing their illnesses. It’s because it’s often the thing that makes them feel less broken.

People with a history of trauma, executive dysfunction, anxiety, or dysregulated mood don’t turn to cannabis because they’re looking for trouble. They’re often looking for relief, regulation, or rest.

What the Galimberti et al., 2025 paper shows—though it never quite says it—is that many of these folks likely share a genetic signature tied to impulsivity, reward sensitivity, and difficulty with top-down cognitive control. These aren’t “cannabis traits.” They’re psychiatric vulnerability traits. And they don’t just drive cannabis use—they drive all kinds of coping mechanisms, good and bad.

The tragedy? When someone uses cannabis for sleep, anxiety, or trauma-induced rage, and the public interprets that as: “See? Cannabis leads to mental illness.” No, friend. Sometimes mental illness leads people to cannabis—because conventional options failed.

It’s Not Self-Medicating. It’s Self-Care.

Let’s call this what it really is: self-care (or self-rescue). Because for many people navigating PTSD, panic, depression, or overwhelm, cannabis doesn’t just dull the edge—it returns a sense of control. A quiet room in a noisy mind.

This is especially true for those failed by traditional models of care. Patients with ADHD who bounce from one side effect to the next. Bipolar patients who hate the blunting of mood stabilizers. Autistic teens whose meltdowns lead to ER visits instead of compassion.

And if you think that’s just anecdotal, you haven’t been reading the clinical literature—or seeing the real-world data.

There are entire clinics, entire cohorts of thousands, whose stories reveal cannabis not as a trigger for madness, but as a salve for a system overloaded by trauma, stress, or emotional chaos.

If the Galimberti paper had layered clinical nuance into their statistical design, we might have seen a very different story.

What the Viral Posts Miss Entirely: The ECS as Mediator

One of the biggest failures in the public interpretation of this study is that it doesn’t even mention the endocannabinoid system (ECS)—despite the fact that this is likely the mechanism sitting at the heart of the genetic overlap.

The ECS is a system of regulation, adaptation, and emotional buffering. And it’s highly sensitive to environmental stress. Trauma can dysregulate it. So can early adversity. So can chronic inflammation, poor sleep, social stress, or repeated psychiatric crises.

Cannabis interacts with this system. Of course it does—it’s designed to. So it makes perfect sense that people whose ECS is running ragged might find cannabis particularly relieving. That doesn’t make it dangerous. That makes it relevant.

For a breakdown on how the ECS mediates trauma and psychiatric symptoms, see:

📖 https://cedclinic.com/cannabis-and-trauma-resilience

The Simplification Scam: Turning Vulnerability Into Villainy

Let’s get brutally honest for a second. When a well-funded organization posts, “See? Cannabis users are genetically prone to psychosis,” they’re not engaging in science. They’re engaging in scientific performance art. It’s the moral panic equivalent of stage magic.

Because the sleight-of-hand is this:

• They ignore the reasons people use cannabis in the first place.

• They pretend CUD and casual use are the same thing.

• They flatten genetic noise into clean causal arrows.

• And they treat psychiatric illness as a rhetorical boogeyman.

But psychiatric illness is not a scare tactic. It’s not a punchline. And it’s not a billboard you can slap on a cannabis policy.

It’s a nuanced, multi-dimensional, sometimes-crippling condition. And how people survive it—the tools they use, the adaptations they make—deserve more than a clickbait headline and a red arrow on a heat map.

When Science Gets Stripped for Parts: How Oversimplification Becomes Policy Poison

Misinformation’s Magic Trick: Sleight of Science

It’s easy to forget that scientific studies are not self-explanatory. They require translation. And translation, like any act of storytelling, is vulnerable to bias, framing, and omission.

When the Galimberti et al., 2025 paper was released, it didn’t say “Cannabis causes mental illness.” But that’s the version the public got. Why?

Because the visual language of certainty—bar graphs, p-values, prestigious journal names—has become a kind of authority costume. And bad actors know how to wear it.

They cherry-pick one correlation (out of dozens), ignore the absence of causation, and wrap it all in a tweet that feels like scientific gospel. Then they let virality do the rest.

But this is not science communication. It’s science exploitation. And it works because most people don’t have the time, training, or tools to interrogate these claims—especially when they confirm a lurking suspicion: that cannabis, deep down, is dangerous.

That’s how we get public health messaging that feels like a fairy tale—complete with villains, magical curses, and a plant that makes people crazy. Spoiler: real science is more complicated than a bedtime story.

What the Message Should Have Been

Let’s try a different version of the headline—one that’s accurate, contextual, and honest:

“New study shows genetic overlap between psychiatric conditions and cannabis use disorder. Findings suggest that psychiatric vulnerability—not cannabis—may underlie problematic use.”

That’s the truth. It’s also less shareable. Because nuance doesn’t spark outrage, and careful interpretation doesn’t go viral.

But here’s the thing: when we trade truth for traffic, we create real-world consequences. People with psychiatric conditions get further stigmatized. Cannabis patients feel ashamed or dismissed. And policymakers armed with bad summaries pass worse laws.

The Real Risk: Weaponized Oversimplification

The biggest danger this paper represents isn’t what it found—it’s how it’s being used.

Because if you can convince the public that cannabis is genetically tied to psychosis, you can do a lot with that fear:

-

Block access to medical use

-

Punish parents who medicate children with autism

-

Undermine funding for ECS research

-

Scare physicians away from recommending cannabis at all

And that’s precisely what we’re seeing. In courtrooms. In state houses. In medical boards across the country.

Yet none of that policy panic reflects the actual weight of the data. Galimberti et al. offered a sophisticated statistical exploration. It’s not their fault the story got hijacked. But it is our collective responsibility to correct the record.

Because when fear becomes the loudest voice in the room, patients suffer.

The Scientist’s Dilemma: Publish or Be Pirated

It’s worth saying this aloud: The authors of the study didn’t commit fraud. They published a high-quality GWAS with careful language and limited conclusions.

But the moment that data entered the public square, it became fodder for manipulation. The authors likely knew that risk—because anyone who works in this space knows how quickly cannabis research gets distorted.

So here’s the challenge for scientists: Do you stop publishing controversial data because someone might twist it? No. But you must anticipate distortion. You must write, title, and structure your findings with guardrails against misuse.

Otherwise, your work becomes the poisoned apple handed out by someone else.

From Villain to Healer: Rebuilding the Cannabis and Psychiatry Conversation

When the Same Genes Point to Vulnerability and Opportunity

Let’s pause for a beat.

What if the genetic overlaps don’t just tell us who’s at risk?

What if they tell us who might benefit most from cannabis—when used wisely, intentionally, and with support?

If impulsivity, trauma sensitivity, and mood instability show up in both psychiatric disorders and cannabis use, perhaps the link isn’t simply liability—but need.

What if these are the very people most sensitive to ECS modulation? The people who can’t tolerate SSRIs, who’ve failed stimulant after stimulant, who’ve tried therapy and still can’t sleep through the night?

It’s not romanticizing cannabis to say this—it’s recognizing that the ECS exists for a reason. And in a system on fire, cannabinoids might be the extinguisher, not the match.

From Disorder to Precision: What the Future Could Look Like

We can—and must—move past the one-size-fits-all model of psychiatric care. And cannabis offers us a glimpse into what precision mental health might look like.

Instead of treating CUD as a moral failing or genetic curse, what if we:

-

Screen patients for ECS sensitivity and stress adaptation markers

-

Match cannabinoid profiles to individual symptom clusters

-

Monitor real-world outcomes through wearable tech or digital journaling

-

Educate physicians on titration, product selection, and adverse event detection

-

Empower patients to know their own endocannabinoid rhythms

That’s not reckless—that’s responsible. That’s how we bring cannabis medicine out of the shadows and into the clinic, armed with nuance and data.

To see this approach in action, check out our evolving clinical model at:

📎 CED Clinic care model

The Real Fairy Tale Is Simplicity

This isn’t a story of cannabis vs. psychiatry. It’s a story about what happens when we flatten complexity for comfort.

Because complexity is scary. It resists slogans. It forces us to confront the messiness of trauma, the mystery of genetics, the individuality of healing.

But pretending the world is simpler than it is—that’s the real fairy tale. That’s the poisoned apple.

And the antidote isn’t panic. It’s precision.

It’s ECS literacy.

It’s remembering that human behavior is not a bug in the system—it is the system.

🍏 A Better Ending

Let’s stop punishing patients for seeking relief.

Let’s stop misreading data as dogma.

Let’s start telling the truth, even when it’s not tweet-sized.

Because fear might sell—but trust heals. And in medicine, that’s the only story worth telling.

What the Headlines Missed: Data Points Worth Your Attention

CUD shares more genetic variance with trauma and neuroticism than with schizophrenia

This matters because the supposed “psychosis risk” isn’t even the strongest signal. Yet media outlets harp on schizophrenia—a rare condition—ignoring more common correlates like trauma, anxiety, and ADHD.

Cannabis Use (CU) and Cannabis Use Disorder (CUD) are genetically distinct

Most people who use cannabis don’t develop CUD. But when CU and CUD get lumped together, as media often do, the nuance disappears—and casual users are unfairly cast as vulnerable or pathological.

The genetic correlation (rg) between CUD and schizophrenia was modest—only about 0.29

That number is meaningful, but not massive. It’s in the same ballpark as the correlation between CUD and insomnia (rg = 0.27), which no one calls a psychosis crisis. Without context, these stats can mislead.

Shared genetic vulnerability doesn’t mean cannabis causes psychiatric illness

Just like some genes increase risk for both smoking and depression, this is about predisposition—not proof of harm. The correlation may exist because people with psychiatric symptoms turn to cannabis for help.

The authors clearly state this is not a causal study

They emphasize that the data are correlational and “hypothesis-generating.” If a reader claims the paper shows cannabis causes psychosis, they’ve missed the most basic limitation of the entire study design.

No consideration of cannabis chemotype, potency, or context of use

The data can’t tell us if it was 5mg of THC or 500. Nor does it differentiate between an anxious teen using CBD at night and a high-potency user with untreated schizophrenia. Without clinical context, conclusions are shaky.

The CUD vs CU difference is critical and almost universally ignored

Cannabis Use Disorder is a clinical diagnosis. Cannabis Use is… use. Most press coverage doesn’t distinguish the two, which is like confusing “drinks wine occasionally” with “alcohol use disorder.”

Psychiatric risk genes overlap across conditions—far beyond cannabis

The same genetic architecture shows up in depression, bipolar, and even risk-taking behavior. That makes it all the more important to avoid cherry-picking findings to demonize cannabis specifically.

No accounting for confounders like poverty, medication use, or misdiagnosis

These aren’t small footnotes. They’re massive sources of bias. Without socioeconomic and clinical controls, genetic signals can become dangerously distorted—especially when used in policy or public messaging.

The biggest risk may not be cannabis—it’s misinterpretation

In the wrong hands, this study becomes a fairytale with a poison apple: seductive, scary, and oversimplified. That’s why this list exists—to pull the curtain back on the data and ask: what does the science actually say?

The Numbers They Never Mention: Cannabis, Genetics, and Psychiatry by the Stats

8%

Estimated heritability of Cannabis Use Disorder (CUD) attributable to common variants in this study—relatively low, suggesting environment, trauma, and social factors play a much bigger role than genetics alone.

0.29

Genetic correlation (rg) between CUD and schizophrenia. Moderate, not extreme. For comparison: the rg between CUD and neuroticism was 0.31—and no one is claiming weed causes personality disorders.

>50%

Percentage of CUD polygenic risk explained by shared risk with depression, neuroticism, ADHD, and childhood trauma. This shows the core signal may reflect underlying distress, not cannabis as a cause.

0.07

Genetic correlation between Cannabis Use (CU) and schizophrenia—barely above zero. This reinforces the importance of distinguishing CU from CUD in both science and public discourse.

0.24

Genetic correlation between CUD and insomnia. That’s nearly the same as the CUD-schizophrenia link, yet no headlines scream “Cannabis Causes Sleep Disorders!” Why? Because it doesn’t fit the scare narrative.

0.17 to 0.31

Range of genetic correlations between CUD and psychiatric traits like ADHD, depression, PTSD, and bipolar disorder—most higher than for psychosis, yet vastly underreported.

4.6 million

Sample size of the UK Biobank–based genetic analyses. Huge datasets, yes—but still limited by the lack of granular clinical data (diagnoses, dosing, symptom response, etc.).

0

Number of causal claims made by the authors. Despite the social media spin, the study authors themselves emphasized correlation, non-causality, and hypothesis generation.

0

Data on real-world cannabis product types, chemovar profiles, or dosage. Meaning the results tell us nothing about how medical cannabis use for anxiety, PTSD, or insomnia actually functions.

∞

Number of times media headlines will reuse the word “psychosis” without reading past the abstract.

Related External Links

Nature Mental Health Full Study

NIH psychiatric genetics overview

CDC, Cannabis and Mental Health

Realm of Care Patient-Oriented Outcomes

2022 meta-analysis on cannabis & psychosis

Related Links at CED

Breakdown of Another Study on the Topic

When Cannabis Might NOT Be Right For You

The Rise of Cannabis Self-Medication Among Neurodivergent Individuals

🔎 10 FAQs about Cannabis and Psychiatric Disorders

1. Does cannabis use cause psychiatric disorders?

No. The Hildebrand et al., 2025 study showed shared genetic traits between cannabis use disorder (CUD) and psychiatric vulnerability—but not that cannabis causes mental illness. Many people with psychiatric symptoms turn to cannabis for relief, not recreation. Causation was not proven in the study, only correlation.

2. What’s the difference between cannabis use and cannabis use disorder?

Cannabis use (CU) simply means using the plant—occasionally or even daily. Cannabis use disorder (CUD) is a clinical diagnosis involving compulsive use, impairment, or distress. Most cannabis users never develop CUD, and the two are often wrongly conflated in research headlines.

3. What is GWAS and how does it relate to cannabis?

GWAS stands for Genome-Wide Association Study. It looks at thousands of genetic variants across individuals to find patterns linked to traits or diseases—like cannabis use disorder. It does not prove causality, only statistical associations.

4. How should clinicians interpret genetic studies about cannabis?

With caution and context. Clinicians should look beyond headlines, evaluate study design, and understand that shared genetic risks don’t equal causation. Clinical care must prioritize patient experience, ECS balance, and symptom patterns—not abstract risk markers.

5. Why is the endocannabinoid system (ECS) important in this conversation?

The ECS regulates stress, mood, reward, and inflammation. Many psychiatric symptoms involve ECS dysregulation, making cannabinoids relevant. Understanding this system helps clinicians interpret cannabis use not as pathology, but as potential self-regulation.

6. Why do people with trauma or ADHD use cannabis?

Because it often helps when other treatments fail. Cannabis can improve sleep, reduce hyperarousal, and support emotional regulation. Labeling this as “substance misuse” misses the therapeutic role cannabis plays for many neurodivergent or traumatized patients.

7. How can studies like Hildebrand 2025 be misinterpreted?

By collapsing CUD and CU, ignoring trauma history, and skipping over confounders. Media outlets often simplify complex data into “cannabis causes psychosis”—a claim the study did not make. This causes public panic and undermines scientific credibility.

8. Is there a safe way to use cannabis for psychiatric symptoms?

Yes, when used with intention, appropriate products, and ECS-informed guidance. It’s not one-size-fits-all. Microdosing, non-intoxicating cannabinoids, and regular check-ins can support safe use in vulnerable populations.

9. How can we improve cannabis research and policy?

By investing in longitudinal, ECS-aware studies and rejecting fear-based narratives. Policymakers must distinguish between misuse and mindful use, and fund education, not prohibition. Research should center patients—not PR.

10. What’s the big takeaway from the blog?

Cannabis doesn’t cause psychiatric illness—but misinformation might. The genetics of vulnerability are complex, and so are the stories people carry. If we care about health, we must care about accuracy.