Table of Contents

- The Perils of Cherry-Picked Science and False Expertise: A Rebuttal

- Biased Sources Don’t Equal Sound Science

- Ignoring the Other Side: What the Author Missed

- Cherry-Picking Evidence vs. Scientific Consensus

- How Real Science Weighs Both Sides

- Confidence vs. Credentials: The Illusion of “Google Expertise”

- The Irresponsibility of Spreading Misinformation

- Summary

The Perils of Cherry-Picked Science and False Expertise: A Rebuttal

Introduction

Charles Fain Lehman’s recent commentary makes bold scientific claims, draped in hyperlinks that, at first glance, seem to signal credibility. Take, for example, his claim that “cannabis has no proven medical benefit” (or insert the actual quote you want to highlight). That’s a sweeping statement—and it’s backed in his piece not by clinical guidelines, expert reviews, or major health institutions, but by selective links from ideologically driven outlets. That’s not how serious scientific claims are made. It’s not enough to cite someone who agrees with you; what matters is whether the broader scientific community, using rigorous methods, has found the same thing.

(Here’s the PDF of the WSJ article)

But the façade falls apart with even modest scrutiny. The linked sources? Slanted. The reasoning? Cherry-picked. The tone? Confidently misinformed.

This isn’t just a difference of opinion—it’s a public example of how pseudoscientific narratives are dressed up as research-backed truth. This rebuttal will do two things:

-

Examine how Lehman leans on biased, questionable sources while ignoring the bulk of real science; and

-

Call out the bigger issue—how easily confidence can masquerade as expertise in today’s media ecosystem.

This isn’t about silencing disagreement. It’s about calling out the method—the irresponsible practice of grabbing whatever supports your view, ignoring the rest, and pretending the science is settled in your favor. That’s not how knowledge works. And it’s not how science is meant to inform public dialogue.

Biased Sources Don’t Equal Sound Science

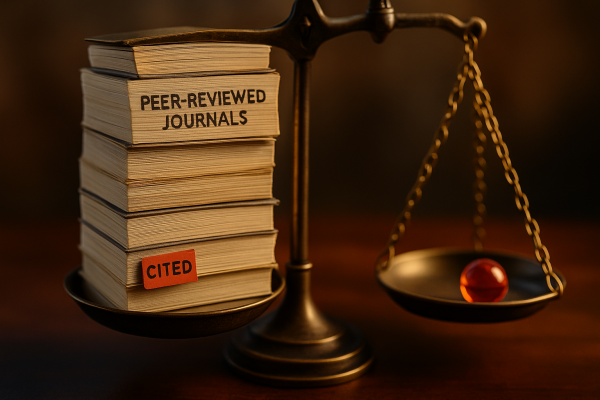

Let’s start with the links. Lehman’s citations overwhelmingly come from outlets that mirror his position. Not neutral institutions. Not peer-reviewed journals. Certainly not anything approaching balance. In some cases, they’re barely more than partisan blogs in lab coats.

Imagine trying to “prove” climate change isn’t real by citing a website called WeLoveGreenhouseGases.com. Absurd, right? But that’s the level of credibility we’re dealing with in parts of his argument—sources that wear their bias like a badge. Some even present as grassroots efforts but are clearly astroturf organizations: well-funded PR fronts pushing a specific ideological line.

This isn’t just weak sourcing—it’s a deliberate narrowing of the evidence stream. Science isn’t a treasure hunt for links that agree with you. It’s the disciplined process of examining all the evidence, especially the inconvenient parts.

Anyone can Google a study or two to make a point. But search engines don’t rank truth—they rank clicks. And when you rely on top results without vetting their credibility, you risk building your worldview on quicksand.

Here’s the thing: cherry-picking isn’t just lazy—it’s deceptive. If you only show data that supports your case and ignore the larger body of work that contradicts it, you’re not revealing insight. You’re constructing a mirage.

To put it plainly: If you need to ignore most of the relevant literature to make your argument sound persuasive, your argument isn’t persuasive. It’s a distortion.

Ignoring the Other Side: What the Author Missed

What Lehman includes in his piece is troubling—but what he leaves out is arguably worse. Science isn’t a one-note song. Nearly every major scientific question has layers: contradictory findings, evolving views, and evidence on both sides. A responsible commentator engages with the full picture, especially when the weight of evidence clearly tilts in one direction. Lehman doesn’t do that.

Instead, he cherry-picks a narrow slice of findings that serve his view, leaving out the vast body of research that contradicts him. That’s not scientific analysis—it’s confirmation bias. And it’s a basic violation of how evidence-based reasoning is supposed to work.

Let’s use climate change as an example. Suppose someone insists the planet isn’t warming and links to a couple of studies or anecdotes about unusually cold weather. What they’re not telling you? That dozens of global, independent datasets confirm rising temperatures over the past century. That over 97% of actively publishing climate scientists agree on the human-driven nature of this warming. That NASA, the World Meteorological Organization, and the American Geophysical Union have all issued consensus statements affirming this reality.

2023, for instance, was the hottest year on record since 1880. The ten hottest years ever recorded? All occurred in the last decade. That’s not cherry-picked—it’s a long-term, globally consistent trend confirmed by multiple independent methods.

Now imagine pretending that this overwhelming consensus doesn’t exist—just because you found one study suggesting otherwise. That’s exactly what Lehman does. Swap in any topic—vaccines, cannabis, nutrition, public health—and the pattern repeats: amplify the outliers, ignore the consensus, and present a distorted version of the debate.

It’s the equivalent of a new drug company claiming its product works wonders, because two small trials had decent results—while quietly ignoring the ten larger studies that found no benefit. That’s not nuance. That’s manipulation. And it’s a disservice to any reader who genuinely wants to understand the science.

Real scientific communication doesn’t cherry-pick. It contextualizes. It admits uncertainty where it exists and explains why certain views are stronger based on the data. By skipping that entirely, Lehman’s argument becomes less a case and more a sales pitch. And when it comes to cannabis, omitting the body’s endocannabinoid system—a vast regulatory network discovered only a few decades ago—isn’t just an oversight. It’s foundational ignorance. This system helps regulate pain, inflammation, mood, memory, appetite, and more. Cannabinoids interact with it directly. You simply can’t have an honest conversation about cannabis’s risks or benefits without mentioning the very system designed to respond to it.

And when it comes to cannabis, omitting the body’s endocannabinoid system—a vast regulatory network discovered only a few decades ago—isn’t just an oversight. It’s foundational ignorance. This system helps regulate pain, inflammation, mood, memory, appetite, and more. Cannabinoids interact with it directly. You simply can’t have an honest conversation about cannabis’s risks or benefits without mentioning the very system designed to respond to it.

Cherry-Picking Evidence vs. Scientific Consensus

Let’s talk about cherry-picking—a term that gets thrown around, but in this context, it’s not just a bad habit. It’s a deliberate tactic that distorts truth.

Picture this: a guy at a fast-food counter orders three cheeseburgers, two fries, and a large diet soda. Then proudly announces he’s eating healthy. That’s cherry-picking. Highlighting the one detail that fits your story while ignoring the mountain of context saying otherwise.

That’s what Lehman does with scientific data. He presents a few isolated studies—some flimsy, some outdated, some likely misunderstood—and holds them up as if they represent the entire field. They don’t. Worse, he offers them without disclosing just how much contradictory evidence exists. That’s not science. That’s salesmanship.

In real research, this tactic is a red flag. The scientific method demands you weigh all the evidence, not just the parts you like. That means giving attention to data that challenges your hypothesis. Scientists don’t stop investigating once they find one study that supports their theory—they look at the full body of work. The patterns. The reproducibility. The quality of the studies, not just their conclusions.

As the New Zealand Science Learning Hub puts it: one person can cherry-pick a study to support their view, but scientists ask a bigger question—what does the total weight of evidence show?

Lehman doesn’t do that. He skips over that entire process. Instead, he builds his argument the way a lawyer builds a case: select only the information that helps, ignore what doesn’t, and make it sound airtight. But science isn’t a courtroom. You don’t “win” by arguing harder—you earn credibility by being thorough, honest, and willing to acknowledge complexity.

And complexity is the key. In most fields, you’ll always find some dissenting views or conflicting studies. That’s how science works. But when one side of the debate is backed by dozens of peer-reviewed, independent studies, and the other is clinging to a handful of outliers, it’s not a balanced debate—it’s a mismatch.

Lehman’s evidence base is like a jigsaw puzzle with most of the pieces missing—and yet he’s claiming the picture is clear. To anyone familiar with research, this looks like exactly what it is: a weak case dressed up with overconfidence and selective sourcing.

If the argument were truly sound, it would stand up to the full range of evidence. It wouldn’t need to rely on obscure studies, vague correlations, or partisan think tanks to make its point. Real science is strengthened by scrutiny. This piece couldn’t survive it. And cherry-picking like this often isn’t accidental. Sometimes it’s ideologically driven—meant to validate a political worldview. Other times, it’s designed for attention: a contrarian take garners more clicks than a nuanced one. But whatever the motive, the result is the same—a distorted version of science, packaged for persuasion, not understanding.

How Real Science Weighs Both Sides

One of the defining features of real science is that it’s slow to make up its mind. That’s not a weakness—it’s a virtue. Scientific consensus doesn’t emerge from a few headlines or isolated findings; it emerges from years (often decades) of back-and-forth: experiments, replications, critiques, refinements, failures, and eventually, a broad agreement among experts about what the data actually supports.

That’s what Lehman misses—or maybe just ignores. His approach is to scoop up a few agreeable data points, ignore the rest, and frame that as settled science. But science doesn’t work like that.

In any evolving field, especially early on, there will be studies pointing in different directions. That’s expected. One paper might suggest a benefit, while ten others show none. So what do real scientists do? They don’t just latch onto the outlier—they zoom out. They look at meta-analyses and systematic reviews that pull together data from multiple sources. They ask: what’s the trend? What holds up across time, populations, methods?

That’s how you separate noise from signal.

What Lehman offers, by contrast, is the opposite of that discipline. It’s confirmation bias with a search bar. He finds what fits and pretends it’s definitive. But let’s be clear: citing one or two fringe studies doesn’t make your argument evidence-based. It makes it cherry-picked. And it misleads the public about what science actually says.

Here’s what a more serious, more honest process would have included:

-

Authoritative summaries from expert bodies. National academies, scientific societies, and institutional review panels often publish consensus reports. These documents synthesize the full range of evidence. Lehman doesn’t mention any. Probably because they don’t support his narrative.

-

Distinctions in evidence quality. Not all studies are created equal. A large, double-blinded trial published in a respected journal means more than a self-published white paper from an advocacy group. Lehman flattens these distinctions, treating weak evidence like it’s ironclad.

-

Acknowledgment of uncertainty. Good science is comfortable with caveats. You’ll hear things like, “This study suggests X, but more research is needed,” or “The findings are preliminary.” Lehman skips that. He speaks in absolutes—confident, final, unqualified. That’s not how actual experts talk.

The irony is, the more someone knows about a topic, the less certain they tend to sound. Not because they don’t know, but because they understand the nuance. In contrast, Lehman’s writing screams confidence, but shows no real sign of grappling with complexity. That’s a tell.

Science is a long-haul process. It favors cumulative knowledge, not quick takes. It welcomes challenges and dissent, but it weighs them properly—by asking not just what a study says, but how much weight it deserves in the bigger picture.

Lehman skips that part entirely. The result is a narrative that sounds researched, but in practice functions more like a house of cards. The scaffolding just isn’t there.

Confidence vs. Credentials: The Illusion of “Google Expertise”

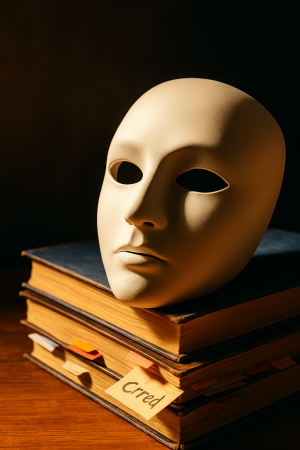

Now we get to one of the most troubling dynamics in Lehman’s piece: not just what he says, or even how he says it—but who’s saying it.

There’s no indication that Lehman holds any formal expertise in the scientific domains he’s opining on. No advanced degree in medicine, epidemiology, environmental science, or public health. No published research. No clinical background. And yet, he writes with the kind of self-assured certainty that would make a seasoned researcher blush.

This is the illusion of Google expertise: the idea that a few hours of skimming search results and Wikipedia entries is equivalent to years of education, training, and peer-reviewed work. It’s the Dunning-Kruger effect in action—those who know the least are often the most confident in their grasp.

It’s one thing to have an opinion. It’s another to pose as an authority in a field you haven’t studied deeply, and to deliver sweeping conclusions to the public as if you speak from equal footing with career scientists. That’s not just misleading—it’s irresponsible.

Imagine a car mechanic who watches a few neurosurgery videos on YouTube and then starts writing op-eds about brain surgery. That’s the level of disconnect we’re dealing with. No one would accept that from a chef, a plumber, or a high school English teacher. And yet in the realm of science and medicine, we’ve created a bizarre loophole where confidence gets mistaken for credibility.

Even more galling is the way this pseudo-expertise is often couched in phrases like “do your own research,” as if the truth is just waiting to be uncovered in the right combination of blog posts and YouTube clips. In theory, encouraging people to be curious is great. But in practice, this often amounts to little more than “find sources that agree with me.”

Without the skills to assess study quality, spot statistical sleight-of-hand, or contextualize findings within a broader evidence base, most people end up reinforcing what they already believe. That’s not research. That’s just algorithmic self-affirmation.

Real experts—actual scientists and clinicians—rarely speak in absolutes about complex topics. They hedge. They say, “Here’s what we know so far,” or “There’s emerging evidence, but more study is needed.” That kind of intellectual humility comes from years of confronting how messy and uncertain knowledge can be.

Lehman’s writing shows none of that. No hesitation. No nuance. Just confidence. But confidence without training isn’t bravery—it’s bravado. And when it masquerades as expertise, it becomes dangerous.

Because here’s what happens: readers who aren’t trained in these fields might walk away thinking Lehman’s version of events is just as valid as that of the experts. They don’t see the blind spots, the missing context, or the flawed logic. They just see citations, strong tone, and a writer who seems to know what he’s talking about.

But the gap between seeming informed and being informed is vast. And Lehman doesn’t bridge that gap—he widens it.

The Irresponsibility of Spreading Misinformation

At this point, it’s not just about cherry-picked studies or inflated confidence—it’s about consequences. When someone presents themselves as a credible voice on scientific issues without the necessary training, and then spreads skewed or misleading claims, the damage goes far beyond a bad opinion piece.

It can lead to real harm.

When readers take Lehman’s assertions at face value—especially on health or environmental topics—they might act on them. And that’s when pseudoscience stops being academic and starts being dangerous. We’ve seen this play out before: vaccine misinformation leading to preventable outbreaks, climate denial delaying urgent policy, miracle cure claims diverting patients from evidence-based care. False certainty, especially when wrapped in scientific language, can cost lives.

The author may not be a public figure on the scale of a national politician or a viral influencer, but the principle remains: the wider your platform, the greater your responsibility to speak carefully. And Lehman hasn’t done that. He’s borrowed the vocabulary of science—citations, studies, charts, jargon—but discarded the discipline that gives science its value: rigor, context, and humility.

And let’s be clear—this isn’t just a “difference of opinion.” Science isn’t a buffet where you pick the facts that fit your taste. It’s a cumulative, collaborative process that filters out the noise to arrive at the most accurate picture possible. When someone strips away that context and presents a handpicked set of results as the full story, they’re not informing the public. They’re manipulating them.

One of the reasons this kind of misinformation spreads so easily is that many people don’t actually know how science works. And that’s not their fault—science education rarely includes how to assess evidence, weigh competing claims, or understand the difference between correlation and causation. So when someone like Lehman simplifies a complex issue into a few tidy “facts,” readers may not realize how many steps have been skipped.

This creates what researchers call “informational residue”—even if the claims are later debunked, some doubt or confusion lingers. It’s why public trust in science erodes over time, even when the science itself hasn’t changed.

And once a false idea is out there, it’s hard to pull back. Articles get shared, quoted, screenshotted. The damage compounds. And unlike real scientists, who update their views as new evidence comes in, Lehman doesn’t appear to leave much room for correction. That’s not thought leadership. That’s narrative control.

Responsible science communication starts with knowing what you don’t know—and being clear about it. If you’re not an expert, you can still write about science, but you have a duty to flag your limits, cite trustworthy sources, and avoid presenting outlier data as definitive. That’s the minimum standard. Lehman doesn’t meet it.

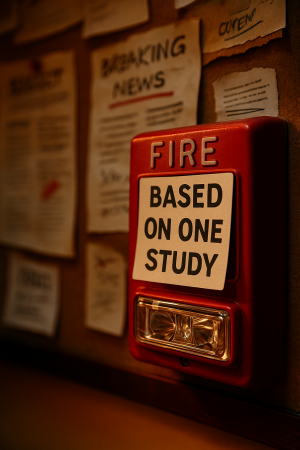

Instead, he delivers bold claims with no warning labels. No “Here’s what others say.” No “This is one view among many.” Just conclusions dressed up as consensus. It’s like shouting “fire” in a crowded theater when all you smell is a blown-out candle. Overreaction without context. Alarmism without grounding.

That’s what makes his piece not just flawed—but irresponsible.

Summary

Science thrives on debate. But that debate has to be honest—grounded in full context, quality evidence, and a willingness to follow where the facts lead. Lehman’s piece doesn’t meet those standards. Instead, it leans on biased sources, omits critical evidence, and packages speculation as certainty. It’s not just the conclusions that are problematic—it’s the entire method behind them.

This isn’t how science is supposed to work. And it’s not how science should be presented to the public.

Lehman’s argument commits the classic fallacy of cherry-picking: lifting a few convenient data points out of a vast field of research, ignoring the rest, and pretending that amounts to consensus. Along the way, he positions himself as an authority without the background, training, or institutional accountability to back it up. Confidence isn’t a substitute for competence—especially when it comes to public health, climate science, or any domain where misinformation carries real-world consequences.

Real science sounds more like this:

“We’ve looked at dozens of high-quality studies. Most point in the same direction. Some don’t. Here’s why we think the consensus matters.”

What Lehman offers is closer to:

“I found three studies on the internet that say what I believe. Case closed.”

That’s not inquiry. That’s performance. And being scientifically literate today isn’t about knowing every detail—it’s about knowing what questions to ask, how to spot bias, and when to recognize that someone’s confidence is hiding a lack of qualification.

As a public, we have to be better at spotting the difference. We need to raise our standards for what counts as credible science commentary—and push back on content that plays dress-up with research while bypassing its rigor.

Takeaways:

-

Check the Source: If all the citations come from fringe blogs or advocacy sites, take a closer look. Science doesn’t live on the margins of credibility.

-

Zoom Out: One study—especially a weak or isolated one—doesn’t outweigh the broader evidence base. Look for consensus, not anecdotes.

-

Beware of Faux Experts: A confident tone and a few hyperlinks don’t make someone an authority. Ask: Do they have the credentials? The track record? The accountability?

-

Understand the Process: Science is cumulative, self-correcting, and full of gray areas. Be skeptical of anyone who claims it’s simple or settled based on a Google search.

-

Recognize the Stakes: Misinformation has a cost. It shapes beliefs, delays progress, and can cause real harm. Publishing half-truths as “research” isn’t harmless—it’s reckless.

In the end, Lehman’s article isn’t just flawed—it’s a case study in how not to approach scientific issues. A better standard is possible. It starts with honesty about what we know, humility about what we don’t, and a commitment to the full scope of evidence—not just the parts we like.

Science isn’t about winning arguments. It’s about getting it right. And getting it right means resisting the urge to oversimplify, overstate, or pretend expertise we haven’t earned. That’s the line between education and misinformation—and it matters. Because science doesn’t reward who shouts the loudest—it rewards who listens longest, questions deepest, and stays humble enough to admit when they’re wrong.

Sources:

-

ScienceUpFirst – Misinformer Tactic: Cherry Picking;

-

The Pitt News – The Death of Expertise and the Rise of Unqualified Leaders (illustrating confidence vs. competence, and a satire of biased sourcing)

-

NASA, Climate Change Scientific Consensus – statement on 97% expert agreement and warming trends

-

Science Learning Hub (New Zealand) – Misinformation, Disinformation and Bad Science (on cherry-picking and how science weighs evidence)

-

Dana-Farber Cancer Institute – Understanding the Spread of Science Misinformation (on harms of misinformation)

Internal Reading

Outside reading: